- Welcome to MUScoop.

Transfers in/out 2025-2026 by The Sultan

[Today at 08:11:45 AM]

Can this team win 4 in a row at the Garden? by Billy Hoyle

[Today at 07:53:47 AM]

2025-26 College Hoops Thread by muwarrior69

[Today at 06:57:20 AM]

Marquette NBA Thread by BE_GoldenEagle

[February 20, 2026, 09:43:56 PM]

2025-26 Big East Conference TV Schedule by Mr. Nielsen

[February 20, 2026, 07:26:40 PM]

2026 Transfer Portal Wishlist by muwarrior69

[February 20, 2026, 04:35:11 PM]

Shaka Smart 02/18/2026 by JTJ3

[February 20, 2026, 04:33:39 PM]

[Today at 08:11:45 AM]

Can this team win 4 in a row at the Garden? by Billy Hoyle

[Today at 07:53:47 AM]

2025-26 College Hoops Thread by muwarrior69

[Today at 06:57:20 AM]

Marquette NBA Thread by BE_GoldenEagle

[February 20, 2026, 09:43:56 PM]

2025-26 Big East Conference TV Schedule by Mr. Nielsen

[February 20, 2026, 07:26:40 PM]

2026 Transfer Portal Wishlist by muwarrior69

[February 20, 2026, 04:35:11 PM]

Shaka Smart 02/18/2026 by JTJ3

[February 20, 2026, 04:33:39 PM]

The absolute only thing required for this FREE registration is a valid e-mail address. We keep all your information confidential and will NEVER give or sell it to anyone else.

Login to get rid of this box (and ads) , or signup NOW!

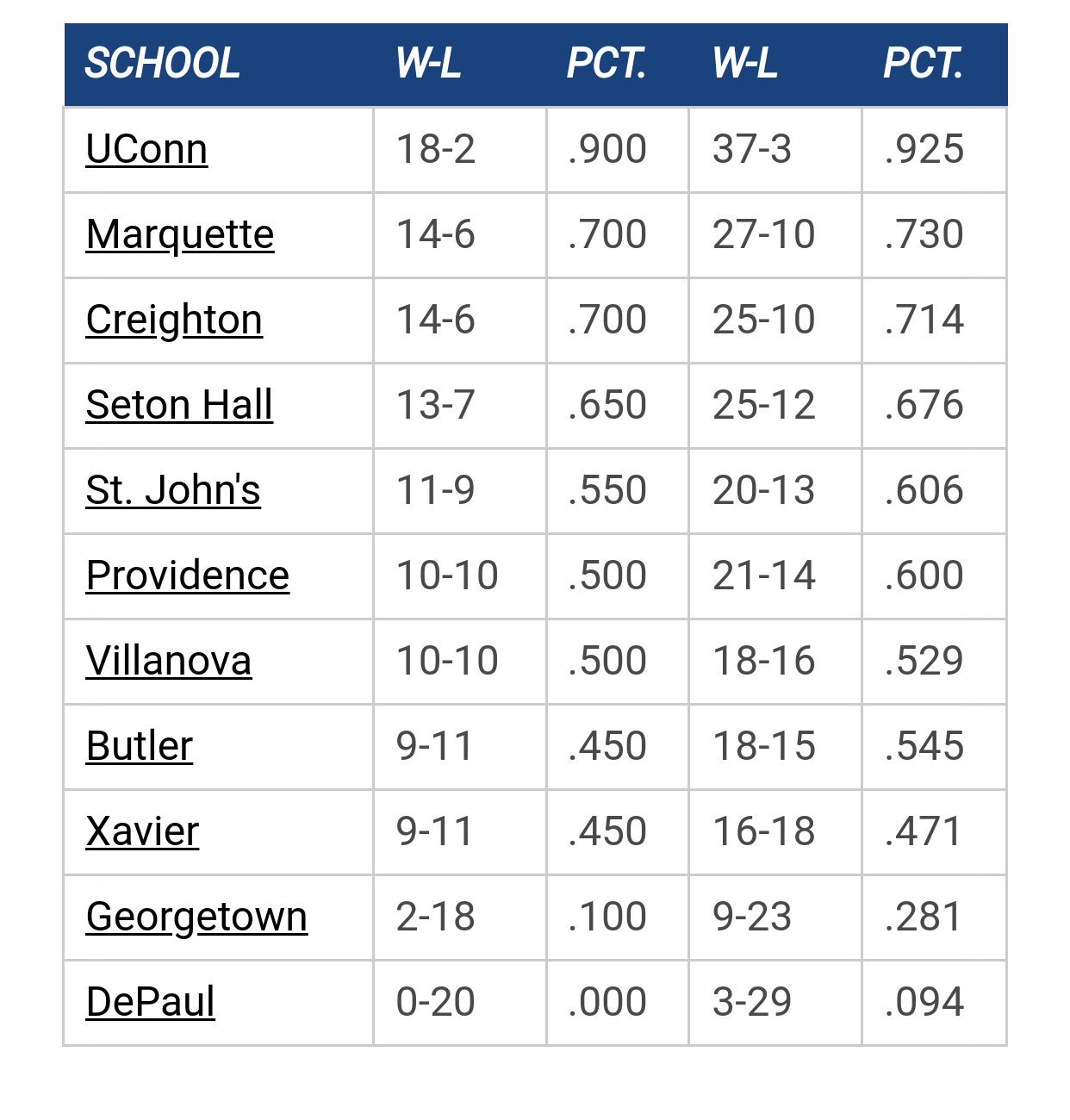

Georgetown Date/Time: Feb 24, 2026, 6:00pm TV: NBC SN Schedule for 2025-26 |

||||||

User actions